A Profile of Roger Casement

When I was a young, naïve seventeen-year-old, you might have found me deep in the mire of Ireland’s standardised testing curriculum: the Leaving Certificate. More likely than not, I would have been hunched over a school desk, writing with fury about a subject that had captured my interest, my imagination, and, most tellingly, my passion. You see, the Leaving Cert demanded that a paper be written on a historical topic—dealer’s choice—and the topic that sparked such fervour in me was the assassination of John F. Kennedy. The ensuing document would be my very first—and, for a long time, my only—foray into historical writing.

This was probably for the best, all things considered. As a young lover of narrative, I fell deep into the rabbit hole of the conspiracy theories surrounding the murder of such a polarising figure. Was the Warren Report really on the level? Was Lee Harvey Oswald really a lone gunman? Or, perhaps instead, real life was more akin to a tale told by director Oliver Stone—one in which varied, vested interests had their sights trained on the painted target on their leader’s back—but which one of them fired the shot? This fledgling historian made the fatal error of believing he had cracked the case, and despite strong guidance from those who knew better, submitted his paper—with pride, might I add—so that it would count towards my overall grade. I came away from the Leaving Cert with a measly C in History. In retrospect, it’s plain to see how such a disappointing result would contribute to the quenching of a passion—perhaps, had I been less enamoured by my own insight, things might have turned out differently (a topic for another post, I’m sure).

In recent years, however, it feels as if that same spark—the one that ignited the passion of a young near-burnout—has found its way to me once more. Finding myself inspired by the myriad works of my favourite popular historians, I’ve decided to try my hand again at writing about history—this time with a wiser head on my shoulders. So it is with that in mind that I must warn you: this post will be of a less philosophical bent, and instead intends to examine the duality of a secret Catholic raised Protestant; a man who would become the progenitor of the human rights activist, and who championed a republican cause all the way to his dishonour and death, only to be posthumously vindicated. Roger Casement was a man who found a voice on the global stage in a time long before the ever-present din of a worldwide cacophony, and through his work, shed light on the horrific injustices that were occurring in places like Africa and Peru. He was also a man strongly divided by nature and nurture, who held extreme nationalistic views and allied himself with some of the darker characters of history in order to further his agenda. The following is a profile of Roger Casement: human rights activist, Irish republican, and traitor to the British Empire.

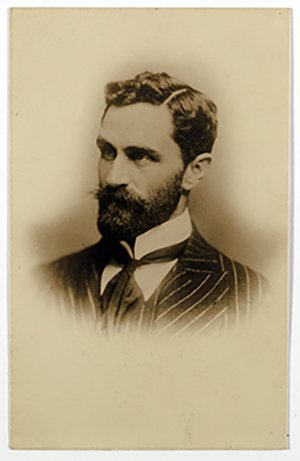

A portrait of a young Roger Casement

Born on 1 September 1864 to Captain Roger and Anne (née Jephson) Casement, Roger spent the first three years of his life in Sandycove, Dublin(1). His father—who had fought with the King’s Own Regiment of Dragoons in the First Anglo-Afghan War in 1842—was an ardent lover of the British Empire and a devout Protestant. His mother, though raised Anglican, was said to have been an even more devout Catholic. When Roger was three, the family moved to Rhyl, Wales, where his mother had him secretly baptised. What effect did such a dichotomous event have on the mind of a growing boy, now even further spread across the expanding chasm of sectarian division? Though only a child, might this connection with his mother and her beliefs have been a sort of tether that would eventually bind him so strongly to his native land and its future pursuit of an independent republic? Later in his life, his writings on Irish Catholics would belie a certain disdain, but as we will learn in time, his perspective would shift dramatically.

In the short term, he would be denied the opportunity to continue such spiritual exploration—his mother passed away of an unspecified illness when he was nine years old. Shipped back to Antrim, his father would also pass a mere three years later(2). He then went to live with his paternal relatives in Liverpool.

As he matured and came into his own, Casement developed an energetic and adventurous personality and was widely regarded as a handsome and charismatic man(3). In spite of the contradictory nature of his upbringing, it appears he did indeed develop an early admiration for the British Empire and, by all accounts, would have been described as a loyal imperial subject. No doubt this was thanks, in large part, to the influence of his father and, later on, that of his paternal relatives. He embraced the notion that colonial rule was the equivalent of forward progress and became convinced of the benefits of the expansion of Western morality. His choice of profession would reflect this globalist doctrine. When Casement was somewhere between fifteen and seventeen years old, he began working for the Elder Dempster Shipping Company as a clerk. A mere four years later, he was working as a purser on the SS Bonny, bound for West Africa. He would make this voyage three times with Elder Dempster before accepting gainful employment with the International African Association in the autumn of 1884(4).

Casement an his IAA colleagues, circa 1884-1891

Those with a keen eye will recognise the name of the aforementioned association. Founded in 1876 by the European powers with the outward intention of advancing science and culture in Central Africa, the IAA would eventually fall under the sway of King Leopold II of Belgium and be used as a vehicle to further his colonial ambitions. Deep in the Congo Free State—Leopold’s private empire—Casement found work with Henry Morton Stanley’s Congo Railway Company, where he conducted surveys for railway construction and supervised labourers. He would also spend this time immersing himself in African culture, learning its languages, and forging powerful and lasting relationships with the locals. It was during his time in Africa—albeit some years later—that Casement was involved in yet another twist of global recognition. In 1890, he would share a riverboat with Joseph Conrad(5), who would reportedly draw on his experience with Casement to inform the creation of his character Kurtz in his seminal novel, Heart of Darkness. The book tells the tale of a descent into the depths of both madness and the Congo Basin, and one can’t help but wonder what Conrad saw in Casement to inspire such an enigmatic and dark character.

But Casement would find more than lasting impressions and deep connections in Africa. It was surely here, in the darkness of the Congo Free State, that he would first become acquainted with the brutality of Empire. He quickly learned the truth behind the International African Association—that it was simply a means for the Belgian king to extract vast quantities of rubber and ivory from the land, and that this was achieved through the exploitation, enslavement, murder, and displacement of the indigenous peoples. He would have borne witness to them being lashed with the chicotte—a multi-pronged whip made from cured hippo hide—or having their limbs removed for perceived disobedience or attempted escape. He would have plainly seen the sub-human standards enforced upon them as their lands were bled dry of resources. What effects, then, did these experiences have on the mind of a young man whose belief in colonialism was built, at best, on a flimsy foundation? Casement would leave the employment of the IAA in 1891. He would spend the next decade working across Mozambique and Angola as a British diplomat(6). It wouldn’t be long, however, before duty would call on him to come face-to-face once more with the atrocities he had witnessed in the Congo Basin.

Casement was serving as the British Consul to the French Congo when, in 1901, the rumours of forced labour, mass murder, and over-the-top cruelty became too loud to ignore; and so the British government petitioned an investigation. Having built up a life around politics and diplomatic circles, it’s quite simple to imagine a young, comfortable diplomat allowing such a calling to pass him by. But something had awoken in Roger Casement. His writings from this period reflect the personal sorrow of his experiences and paint the portrait of a burgeoning advocate for human dignity(7). Accordingly, he volunteered to lead the investigation into the International African Association.

King Leopold II of Belgium would become an international pariah for his actions in the Congo Basin

Beginning in 1903, Casement travelled deep into the Congo interior, where he conducted first-hand interviews with local residents, tribal chiefs, religious missionaries, and even officials of the Congo Free State. He collected eyewitness statements, supporting documentation, and took meticulously detailed notes on what he found there: an institutionalised system of resource extraction built squarely on the abuse and suffering of the land’s native peoples. The Casement Report was published in 1904, and would later contribute to the annexation of King Leopold’s territory by the Belgian government in 1908. Casement was praised for his objective, unemotional writing—supported by facts and evidence—combined with clear and heartfelt descriptions of the atrocities and violations visited upon the local population(8), and his report served as a lightning rod for Western outrage at what was taking place. In 1910, Casement was petitioned by the Crown to travel to Peru to once more investigate reported human rights abuses, this time at the hands of the Peruvian Amazon Company. This endeavour led to the publishing of The Putumayo Report, earning Casement even further acclaim, and ultimately, a knighthood.

The voice of his conscience would not be silenced so easily, however, and in the intervening years, his feelings of duty and obligation could only have hardened before they began their long—but interminable—march to the north-west. While on leave from his station in Africa in 1904, Casement returned home to Ireland, where he joined the Gaelic League, a society intent on stoking the fires of Ireland’s social and cultural revival. A year later, he would join Sinn Féin, the new political party founded by Arthur Griffith with the express intention of achieving Irish independence through strike and boycott. In a letter dated April 20th, 1906, Casement reflects on his British assimilation, and on his rediscovery of himself as an “incorrigible Irishman”(9) due to his experiences in the Congo and the Boer War. Casement’s tectonic shift in perspective during these years would help contribute to the fresh foundations being laid for his later turn towards full-tilt republicanism.

Tired and sickly from his years of travel, Casement retired from the British Consular Service in 1912 and returned home to an Ireland racked by political upheaval, violence, and anti-British sentiment. No doubt he would have looked upon his homeland and compared the atrocities being visited upon it with those of the colonialism he had witnessed in Africa. He became involved in the politics of Ulster, positioning himself as the opponent of Edward Carson and becoming a fervent supporter of Home Rule. As time passed, Casement wrote articles in The Irish Review(10), deriding moderate nationalism and setting out his views on Ireland’s right to complete and total independence. In 1913, he joined the Irish Volunteers—a paramilitary organisation founded in response to the creation of the similarly named Ulster Volunteers, who themselves had been formed in opposition to the same Home Rule movement Casement so strongly supported—as a founding member of their Provisional Committee. Perhaps this stark, rapid tumble towards hardline nationalism might be explained by the addled conscience of a man suffering from the myriad ailments acquired on his exotic travels, and his desire to wipe it clean before his incipient death; or perhaps, more likely, the effects of the travesties he had witnessed had simply convinced him that like must be met with like. In 1914, he travelled to New York with the express intention of raising funds and acquiring weapons for the Irish Volunteers.

It was here that Casement began to work with John Devoy. Devoy was a former member of the Irish Republican Brotherhood and had taken part in the Fenian Rising of 1867—although by 1914, he was the owner and operator of The Gaelic American, a weekly New York newspaper. It was through Devoy that Casement became involved with Clan-na-nGael, an Irish-American republican organisation founded by descendants of Irish immigrants—now with very deep pockets—in support of an Irish Republic. Though their relationship began frostily, Casement would go on to earn the respect and admiration of his new colleagues—not least through the successful execution of operations such as the Howth gun-running(11) in July 1914, in which Casement recruited the assistance of writer Erskine Childers to deliver 1,500 bolt-action Mauser rifles to the shores of Dublin. It’s not difficult to imagine a man of growing confidence and esteem on the back of such success; Casement would need to seize this momentum, however, as the shot heard around the world would soon ring out. By August of 1914, Europe—and the world—was officially at war.

Casement went to work arranging a meeting between himself, Devoy, Clan-na-nGael, and their tentative guest of honour: Count von Bernstorff, the top German diplomat in the United States. His logic was simple: the enemy of my enemy is my friend, and if the British were busy dealing with civil unrest on the island of their second capital, then this would mean fewer resources to throw at the Western Front. In return, they asked for arms, ammunition, and experienced military leaders—men who would help hone the Irish nationalists into a fighting force. Though no formal agreement was reached at the time, von Bernstorff did express strong sympathies. And so, inroads were made; these opened the path for Casement to travel on a Clan-na-nGael-sponsored trip from New York to Germany in 1914, with the express intent of raising a brigade of soldiers from the Irish prisoners captured in the early months of the war(12).

Casement failed spectacularly. Of the roughly two thousand Irish POWs in Germany, he managed to convince a paltry fifty-six to turn their backs on the Crown and join their German captors—one can’t help but wonder whether Casement and his co-conspirators overestimated the level of hatred the average Irishman held for the British Empire, or perhaps underestimated their fear of it. Though his mission to raise an army proceeded poorly, he remained in Germany still, intent on pressing for the oft-promised weaponry and support. Germany did finally offer Casement what he was looking for: twenty thousand Mosin-Nagant rifles—relics of a bygone age—and ten modern machine guns, with all relevant accoutrements. They would deny him his request for experienced personnel, however. In exchange for this equipment (and a promise that an independent Ireland would never suffer aggression at Germany’s hands), the State Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Arthur Zimmermann, requested Casement’s formal renunciation of his titles and ties to the British Empire. On December 27th, 1914, he signed such a declaration and had it delivered to Zimmermann’s British counterpart, Sir Edward Grey. Roger Casement had officially declared himself a traitor.

Over the course of the succeeding eighteen months, Casement would spend his time continuing to raise and train the Irish Brigade from those who might cast off the shackles of their oppressors, while back in the homeland, the Irish Volunteers were busy formulating plans that would make heavy use of the promised weaponry. These schemes would eventually evolve into an island-wide rebellion known as the Easter Rising. Working with the Germans and his counterparts back in Ireland, Casement made arrangements for the arsenal to be delivered to Ireland on a sailboat by way of Tralee. From there, the guns would be distributed across the country and used to fan the flames of revolution up and down the island.

Unfortunately, this confluence of events was never to take place. Dogged by communication and logistical issues, the Aud(13)—the ship ferrying the weapons across the Channel—departed behind schedule, and as such would not arrive in time for the beginning of the Rising. Though Casement made efforts to alert its leaders, to implore them to postpone, his warnings would not arrive in time—or perhaps they simply fell on deaf ears. Worse still, the Aud did not receive the expected signal from the Irish Volunteers when they arrived in Tralee. As such, they tarried suspiciously in the port for a full day before drawing the attention of HMS Bluebell on April 21st, 1916. When commanded to sail into Cobh Harbour for inspection, the captain of the Aud did so, but upon arrival scuttled the ship so as to prevent the capture of its payload. Its crew were arrested as prisoners of war, and the Mosin-Nagant rifles found a new home at the bottom of Cobh Harbour.

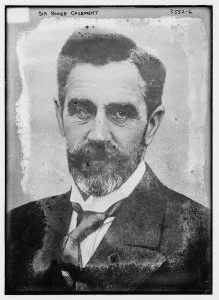

A portrait of Casement in his later years

Casement’s own fate would be all too similar. He would make the precipitous journey back to Ireland in a German U-boat. Still harangued by the long-standing illnesses acquired over the course of his extensive travels, he would have no doubt been a pristine picture of poor health amidst the narrow, coffin-like steel chambers of the prototype submarine. Though the original plan was to rendezvous with the Aud, readers will not be surprised to learn that fate had other ideas. On the same day the ship was scuttled, the German U-boat U-19 was forced to land on Banna Strand in County Kerry, where a slow and sickly Casement disembarked. From there he travelled inland as far as Rahooneenan, before attracting the attention of the Royal Irish Constabulary(14). When they learned he was in possession of three small firearms, he was taken into custody on a charge of weapons smuggling. The Irish Volunteers would make no attempt at a breakout; they had express orders not to fire a single shot until the Rising—orders which were followed.

Instead, Casement was taken back to England and placed on suicide watch in Brixton Prison. His trial would begin on June 29th, 1916, and although the prosecution’s poor showing raised hopes of an acquittal, an oblique interpretation of the Treason Act of 1351 meant that Casement’s deeds in Germany—although occurring on foreign soil—still counted as treason against the British Crown. He was sentenced to be hanged, and while his work as a renowned diplomat gave his appeal a strong chance at success, he would be the subject of a smear campaign at the hands of British Intelligence(15). They released what they purported to be copies of his secret diaries—diaries which detailed the life of a “sexual deviant,” one who took part in homosexual activities and solicitation. Casement lived in a world where this type of behaviour was not just morally reprehensible, but outright illegal—as such, any goodwill he had earned through his activism was washed away like deadfall in an angry river. The man was officially stripped of his knighthood, and on August 3rd, 1916, having been received by two Catholic priests—as clear an echo of his spiritual duality as we have—Roger Casement was hanged by the neck until he died. He was fifty-one years old.

The hanging took place in Pentonville Prison where, in defiance of the man’s final wishes to be repatriated to Ireland, he was unceremoniously buried in quicklime. Through multiple formal diplomatic requests for exhumation and removal on the part of the Irish government, Casement’s remains would stay there for decades. In time, Éamon de Valera and Winston Churchill would argue over such strict adherence to the letter of British law and the resentment it instilled in the Irish people. It wasn’t until 1965 that his remains were repatriated to his home country, where he received the full state burial—with military honours—that a man of his accomplishments deserved.

Casement on trial in 1916

Roger Casement left behind a somewhat rocky legacy. One could confidently refer to him as the first human rights activist, and through his work in the Congo Basin, Peru, and other parts of the world that were suffering under the thumb of empire, he made great strides in publicising the damage unchecked colonialism wreaks. He was a man born under the Protestant star who died in the company of Catholic priests. While the life painted in the details of his Black Diaries—the title of the publication of his private journals—appears quaint by our modern lights, his contemporaries would have viewed such behaviour with scorn, contempt, and ridicule. This, coupled with his extreme perspective on nationalism—and his distaste for empire—surely painted him as a polarising and divisive figure.

In our modern world, however, Casement has largely been vindicated. He is seen by many as the father of anti-colonialism, and although he made strange bedfellows with many villains of history, Roger Casement proved time and time again not only his noble desire for an independent Ireland, but his deep compassion for his fellow man. In both Ireland and in Africa, he is celebrated with statues and street names, airports and housing estates. It’s hard to deny his determination in the face of some of humanity’s worst crimes—something even his greatest enemies could appreciate. We need look no further for evidence of this undeniable respect than what was written on the consignment of the man’s remains when shipped back from their internment in Britain: “The Remains of Sir Roger Casement”(16).

References

https://www.nli.ie/1916/exhibition/en/content/rogercasement/

https://modernismmodernity.org/articles/metamodernist-archive

https://www.amazon.com/Eyes-Another-Race-Casements-Report/dp/1900621991

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/casement-report-documents-violence-in-congo/

https://theanarchistlibrary.org/library/jack-white-where-casement-would-have-stood-today

https://centenaries.ucd.ie/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/Supplement-3-Roger-Casement.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2000/may/02/richardnortontaylor